As adults, caregivers, and parents alike, we begin to guide young children as they interact with other children. We want our children to be kind, empathetic and caring towards others.

So, when your preschool or toddler walks over to another child, snatches their ball, and runs away. The other child begins to cry. What do you do?

It is very natural for parents and caregivers to jump in and tell the child to “say they are sorry”. However, just saying “sorry” without follow-up teaches children that they can act on impulse. Just saying “sorry” is actually permission to do it again.

“If I say I am sorry afterwards, I can do it again next time and just say sorry.”

This is the message that is sent. Parents can do much better.

Following these few steps working with children not only gives young children language to use, but also helps them through the process. This is a good beginning to a life long journey of becoming an empathetic and caring human being.

Try this easy 6-step process.

First, make sure the child who is crying is involved. Give a hug, and together approach the child who took the ball:

This may seem like it would take a long time, but the entire interaction should take about a minute or two. Taking any longer won’t hold their attention and lose impact.

Be prepared and ready. You might learn that something else happened prior to you seeing the child take the ball from Susie. You might hear that Susie had done something else to upset the child. In these cases, take the time to listen and help the children work it out.

Practicing this with consistency is important. Also spending time with children, when there is no conflict, helping to identify emotions and connecting to words is a good exercise.

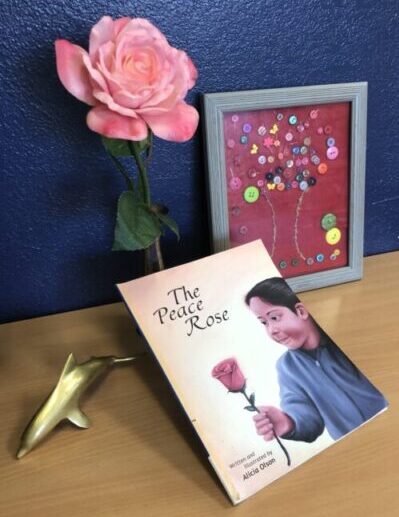

At the Montessori School of Silicon Valley, we introduce the Peace Flower/Peace Table to children after the age of four. We will often see older children helping the younger children with the peace flower. This can be beautiful to watch.

When there is a disagreement between two children, one strategy is the use of a Peace Flower. The Peace flower is an item in the classroom, it may be a fresh flower in a vase located on the Peace Table. Or it can be a object in the classroom like a fragile statue that sits on a shelf. When children have a conflict, the guide will first ask them to “please go to the peace table and use the peace flower”. Children learn to take turns holding the Peace Flower while speaking about how they feel. They stay at the Peace Table or with the Peace Flower until they have heard each other and resolved their conflict.

With very young children, adults model and coach the children with words they can use. This is generally done at group time, giving the lesson when the lesson is not needed. This is important. Teaching “how to resolve conflict” when there is a conflict simply does not work.

But what happens when there isn’t peace?

I was on the playground, it was 1995, I was in my Montessori teacher education training and we had just learned about the “Peace Flower”. The guide in the classroom had introduced the Peace Flower to the children. They used it on the playground.

Here is what happened:

One boy had a special rock, apparently, it lived in his pocket. Another boy, got ahold of this rock and threw it over the fence.

Out comes the peace flower. The boys used their words, shared their feelings, and got to the bottom of the issue. At the end, the guide says. “Shake hands and say, let’s be friends”. The boy, the one who threw the rock, says “lets be friends”. The other boy said “no, you are not my friend”.

The guide did not know what to say. What might have been a better ending?

Simply stating “let there be peace?”.

By saying “let there be peace” allows the child to have some space, he might need some time to get over losing his special rock.

It is important to allow children to have their feelings. Not every conflict can or should resolve immediately. In this situation, it can be agreed upon, “let there be peace”. And the boys do not have to go back to the way it was prior to the rock being thrown over the fence. It should be ok if they take some space apart. In time, it will work itself out. As adults, we also need to allow children time for this.

With parents and caregivers working together to give the children the words, attaching the words to emotions, the children will start working issues out without adult intervention. When this starts to happen, it is important to:

That’s it! Leave it there. No need for more words.

There is no need to say, “Good Job”.

Children Are Wired For Empathy

We Shouldn’t Make Young Children Say Sorry

Here’s What Works Way Better Than Forcing Your Kid to Say Sorry